The First Online Sports Game

Netrek is Mind Hockey on the Net

(Original article published in WIRED magazine, December 1993)

On any one day, about 5,000 people will find their way to a couple of nodes on the Net and pick up a game of Netrek. Playing Netrek is like playing team chess on speed, or playing mind hockey. At first glance, the game's spare and simple graphics resemble the classic old '70s video arcade game, Spacewar. But Netrek bears all the marks of a raging '90s phenomenon: It's graphical, it's played very, very fast, and it is played in teams, on the Net.

Someday we'll look back at the videogame era of the 1980s and '90s, and wonder why anyone played solitary games. How Dull! How sorry.

In Netrek, you storm planets in a squadron of ships piloted by you and your teammates. You sit at your console and when you fire a missile, everyone else playing the game, whether they are in Denmark or Pittsburgh, watches it zing to its target. Sixteen people romp in intergalactic real-time dogfights.

Netrek was invented by Berkeley undergraduate students Chris Guthrie and Ed James about five years ago. It began as a game called X-Trek and was played over the campus network on X-windows machines. That early version was later revamped into Netrek by three other Berkeley students, Scott Silvey, Kevin Smith and Terence Chang. Now there's a league - The International Netrek League (INL) - with eighteen teams that engage in weekly games and seasonal playoffs. Chang went on to graduate work at Carnegie Mellon University, and now CMU and Berkeley are the heavyweight teams in the Netrek League. CMU has a reputation for "playing with an attitude and being into big ships," Chang says.

Team names sound like names of bands. The CMU team is "EIEIO." Los Angeles has "Will Riot for Food." Seattle has "Lagg U," a joke on the frustrating time delay that long-distance Internet play sometimes induces. The Berkeley team calls itself the Golden Bears, in mock reference to the Berkeley sports program. Most of the Berkeley guys are former students who gather every Saturday afternoon in the computer science building to play in cyberspace. They probably could login from their home nodes, and sometimes they do, but in a very telling reversal of what we expect from network culture, they like to drive once a week to the campus and cram themselves into a couple of work cubicles to play each other over the Internet, and then go for a beer afterwards. Could be an Iron John thing.

I like to think of Netrek as the first online sports game. Two teams of eight players meet in a Netrek arena - a local "galaxy" with 40 planets in it. The object of the game is to capture the planets by ferrying troops onto them. So while you and your seven teammates are trying to transport your armies to the far edge of the galaxy, the opposing team is sacking your established planets and filling them with its troops. The overt military plot won't win any theme awards, but as I said, the game is like team chess. The thrill comes from the thousands of moves, set-ups, and real-time team plays that can happen in this spare, almost archetypal game.

Like chess pieces, there are different kinds of space ships with different powers and moves. The current standard version of Netrek has six varieties. One ship type can haul lots of troops, but slowly. One ship has lots of fire power but no endurance. One ship is fast but small and has fuel-costly defense shields. And each ship might have choices in armaments. For instance there are two kinds of weapons. You can fire a laser that hits its target instantly; but, since it is light, the power of its impact decreases geometrically with the distance of the target. Or, you can fire a torpedo- like missile; its power won't diminish over distance, but because it takes time to travel you need to anticipate the inertia and countermoves of the target in order to hit it.

There is an option to create a stealth ship by donning a cloak of invisibility. This allows a number of interesting attack formations. But it uses up tremendous virtual fuel.

The sport thus becomes a fast-paced game of strategy and tactics not unlike basketball. Team members charge toward a planet in a kind of power play. The defense responds in its well-practiced formations. But in Netrek there are twenty or more balls loose on the court, so it can get pretty frantic. "Team play is very important," says Scott Northrop, a Seattle player. "Several roles have evolved over the years, like deep bomber, planet taker, escort planet taker, kill enemy planet taker. And there are a bunch of maneuvers that everyone knows, such as the 'ogg' - jargon for a suicide attack on an important enemy player, or the 'base ogg' where everyone kamikazes on the enemy starbase (when your ship blows up, it causes damage to everything around it)."

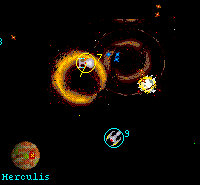

Each game last 90 minutes. For an hour and a half, eight guys (99 percent of the players are male) frantically pound on keyboards. (One Netrekker half-joked that the game is the leading cause of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome among computer science grad students.) The monitor for each player displays four windows. One portal is the inclusive galactic view of all the ships and planets. A second window displays the other ships from the specific view of the player's ship. A third window records the current status (armament, power, fuel, load) of all players. The fourth window scrolls up with a record of the live typed conversation teammates communicate with (instead of the two-way radios they should have).

The eight players on a team can login from different parts of the country, or even different countries. Their eight opponents may likewise be scattered in geography. Usually a team will cluster at a school or the computer department at the employer of one of the players. Netrek requires an X-windows workstation for each participant (other versions are on their way), and a direct Internet feed (a slow modem can get you killed); that means a more expensive computer than most players own, so the team heads to a corporation or campus off hours where a bunch of nice Sun Sparc workstations mainlined into the Net are sitting idle.

The little orbs that represent planets in the galactic view on the Netrek screen change color as one team successfully wrenches them from the possession of the other. To an observer, it's pretty subtle.

When they are within yelling distance, teammates enjoy high bandwidth communication. Typical overheard dialogue: "Get forward, flea!" "Man, that's grim." "Okay, we got a base!" "Hey, I just died taking one of them out." "Base ogg my next ship!" "Guys, if you're not scumming, I need bomb help!" (The term "scumming" is the sport's slang for capturing a planet).

The little orbs that represent planets in the galactic view on the Netrek screen change color as one team successfully wrenches them from the possession of the other. Micro-sprites hover around the planets like buzzing mosquitoes; these are the ships in play. To an observer, it's pretty subtle - sort of like watching checkers. In a blink the blue team can force the red squadron to circle a planet until the fuel for its shields runs out and then cream them, all while you looked away.

Like any thinker's game, experience counts. It ordinarily takes at least one year of weekly Netrek playing to get up to league skill.

Tom Holub, one of the game's "old men" at 24, has been playing weekly, and sometimes daily, for years. He even confesses to having played round the clock on weekends in the past. He recounted for me the finale of a recent game. "We had only two ships in the area; not very good odds. Two of us just stayed cloaked by the planet trying to avoid enemy fire (once they hit you with a phaser, they can see exactly where you are, even if you're cloaked.) We waited until the last possible second, uncloaked, fired everything we had and detonated all the enemy torpedoes. We set off a beautiful chain reaction; four of the escorts blew up, and their explosions killed the army carrier, saving our planet. Unfortunately, we still lost, but it was a fun game."

What seems to please the players of Netrek the most is that this is open software, subject to improvements by the players. "Pity General Magic and Nintendo and those guys who don't have programmable, open-architecture boxes - they'll never get something with the neato factor that Netrek has," says Scott Northrop, a Netrek contributor. "We share our creations because we want others to improve them, show us the parts we forgot to program into them the first time, finish the great idea that we've gotten burnt out on. That is what happens when you give thousands of adherents to the Hacker Ethic access to capable hardware, and a net to connect them."

The future of Netrek might be gizmos called borgs, fabricated by the loose network of net-game programmers. Borgs (short for cyborgs) are AI helpers. Since Netrek is public domain software, some players have hacked artificial intelligence routines for common plays. These guide the ships into certain moves when they detect the proper conditions. But veteran players scoff at the usefulness of borgs in championship play. "You can always tell when someone is playing a borg," a five-year Netrek veteran told me, "and then you can outsmart them. The only ones who use borgs are beginners - they are borg weenies."

"The thing that I love about playing Netrek," a player named Scott told me, "is that you're not playing a computer. You're playing teams." Someday we'll look back at the videogame era of the 1980s and '90s, and wonder why anyone played solitary games. How dull! How sorry. That episode will be a pathological quirk in the history of games - which have always been multiplayer, and soon will always be so again. The convergence of multimedia, television, and interactivity is landing on electronic games, and not electronic work. And the future of games is multiplayer games. That's why AT&T, Warner Communications, and 3DO are watching Netrek and its quickly emerging cousins. Imagine if every Nintendo unit was plugged into the Internet, and you'll get some idea of the fun and profit about to be born.

If you want to try Netrek without being a borg weenie, you can read the newsgroup rec.games.netrek. To join a pickup game, try going to the "Metaserver" at Scharon.amdahl.com 3521 [which has moved to metaserver.ecst.csuchico.edu 3520 --ed.] to see where the several games of that hour are. Port 3524 at charon.amdahl.com dumps out the Frequently Asked Questions on Netrek. For equipment, best is an X terminal, preferably color, preferably large. There is a Macintosh version and a Linux version playable on IBM PCs; details from rec.games.netrek.